This is a just a quick note in answer to some questions. More detailed article to come!

I had this tent custom-built in 1986.

I wanted it to be made of the traditional (wonderful) Egyptian Cotton, but it was not available. So I theorized that I could get almost the same light weight and small folded-package-size if I made the tent from lightweight uncoated rip-stop nylon (so it would breathe a bit), but have the stove-corner made of the horrible modern 11 oz fire-retardant polycotton that the tent manufacturers were switching to.

It worked! I’ve set it up in the Bush hundreds of times. It’s a bright, airy, comfortable home-away. Feels good to live in it.

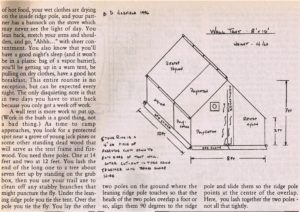

In use, when you step into the tent you usually step down. This is the working-area, and also serves as a cold-sink at night — you dig the snow away here and throw it into the sleeping-area to raise it (before you lay down the ground-sheet). On your left is the wood-stove, on your right is the grub-box — it’s hinged lid rests on a stake to give you a level table-top.

Details: the floor plan is 8 x 10. The sidewalls are 3 ft, and the peak is 7 ft. It was built by Manitoba Tent and Awning, to a very comprehensive Plan I gave them. It weighs 14 lbs and folds up into a small grain-sack that easily fits on a sled. It’s a good rig, and I wouldn’t change much if I was replacing it.

There is a window in the back peak corner, with sewn-in no-see-um netting, for ventilation, but it is not open unless you unzip the nylon away from it. This can be handy during spring or fall set-ups when the tent is getting too hot.

There is no floor, nor should there be. (A sewn-in floor is a pain in a winter set-up.) It has sod-cloths, which are poly flaps that are attached to the side-walls. You pull them out in winter and heap snow on them for an airtight seal. In spring and fall you pull them inside and put your ground-sheet over them. These sod-cloths are of poly, but should be the more dense 14×14 weave, not the cheap stuff. And they should be 24″ in length.

For a ground sheet in the back half of the tent, the sleeping-area, I use Typar house-wrap. Wonderful stuff. Light, quiet, warm, it doesn’t slide around like a poly tarp does, and is waterproof enough for winter camps. I use tuck-tape to join the Typar to get the right width. I also use a small square of it to stop melt-under the stove, since Typar is very fire-resistant.

Zippers are bad on the front door of a wall tent. The set-ups are not always perfect and a zipper wouldn’t always align. (And there are no bugs anyway.) Rope ties are much better. The are simply 1/4 ropes that thread through the grommets, and have a stopper-knot tied in each end. This allows you to tie the entry closed from inside, or outside. The grommets are in a staggered pattern, a zig-zag, which produces a better air-seal than if the grommets lined-up directly under each other.

Sewn into the ridge-line from the inside are stout nylon loop-straps, which are used to hold interior ridge-poles for drying clothes and sleeping-bags; birch or alder saplings, usually about 1″, smooth-barked — 2 of them, with an overlap in the center. This works much better than a rope — a rope pulls the ends of your tent into the center when you hang a bag from it.

This stove-thimble is actual authentic vintage asbestos — great stuff! 😉 but these days you’ll have to do something different. But it should definitely be in the door, NOT the roof. Having it in the door means there is no hole in your roof, or the fly-sheet, and it wires conveniently onto the ridgepole. All the sparks are vectored away. No need for a spark arrestor to clog-up your stovepipes.

There are mesh pockets in the sidewalls for your glasses and headlamp and rubber bands and such. I should have had 2 more sewn into the backwall.

It takes 2 people about an hour to walk into untouched bush and get the tent up, the stove installed, and water boiling — in a good site. If you have 3 people even better — you’ll have a pile of firewood cut as well, and a tidied-up camp with gear put-away for the night.

Yes, this is more work than a dome-tent, but work in the bush is not a bad thing. And this tent is a comfortable, low-stress way to live. You can put up with almost any conditions during the day if you know that you will have a chance later to rest in a warm place, dry your boot liners, have a hot meal in comfort, get into a dry sleeping bag, awake in a warm space, put on dry clothes (and gloves and hats), eat a hot breakfast with multiple cups of tea, and start the day right. You laugh at the gales!

I used to write a column for Bushwhacker magazine called “Practical Bush Gear”. Recently I dug out my 1997 article describing these tents. Here are the scans. They are old, but not much dated.

.

.